Daily Energy Compensation Patterns

Mechanisms of energy adjustment and intake regulation in response to dietary changes

The Concept of Energy Compensation

Energy compensation refers to the body's theoretical ability to adjust energy intake in response to prior intake or energy expenditure. If a person consumes excess energy at one meal, compensation would manifest as reduced intake at subsequent meals, resulting in roughly equivalent daily energy totals.

Conversely, research examines whether consumption of discretionary foods triggers compensatory reduction in other eating. If compensation were perfect, consuming a treat would result in equivalent reduction of other foods, leaving total daily energy unchanged. In reality, compensation is often incomplete.

Understanding patterns of compensation (or lack thereof) provides context for how discretionary food consumption affects total daily energy balance.

Acute Compensation Studies

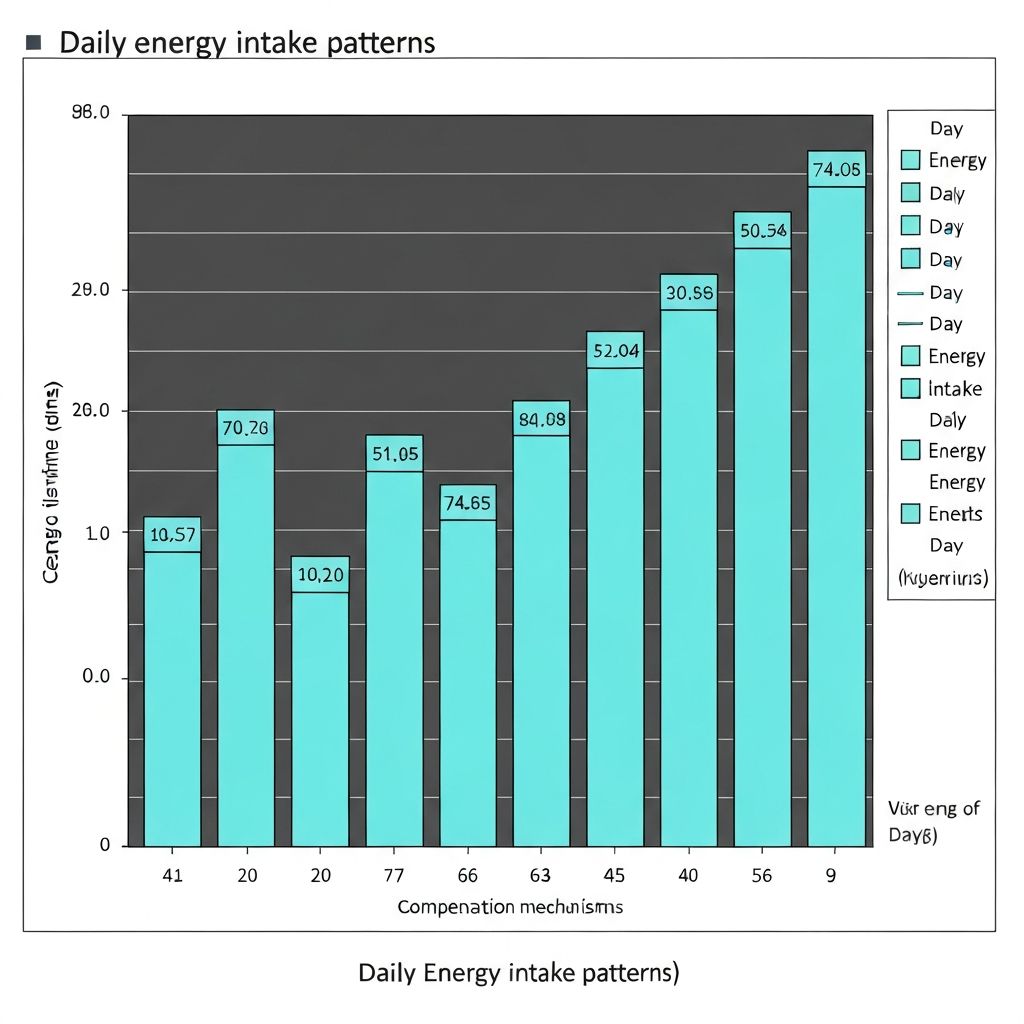

Research examining acute compensation—changes in intake on a single day in response to prior eating—documents variable findings. Some individuals reduce intake of other foods following consumption of high-energy treats; others show little or no compensation.

Intervention studies where participants consumed fixed amounts of high-calorie foods (e.g., sweetened beverages, snacks) and were then observed during ad libitum eating periods reveal that compensation ranges from complete (energy from the provided food is offset by reduced intake of other foods) to negligible (no reduction in other eating despite high energy from the provided food).

Several factors influence the magnitude of compensation: the type of food consumed, the duration between eating occasions, individual sensitivity to satiety signals, and contextual factors such as stress or environmental food cues.

Compensation and Food Type

Different foods produce different compensation responses. Liquid calories (e.g., sugary beverages) typically produce less compensation than solid foods—people frequently fail to reduce solid food intake when consuming liquid calories, resulting in net energy surplus.

Foods consumed outside of traditional meal contexts may also show less compensation. A treat eaten between meals may not trigger reduced intake at the subsequent meal the way an extra serving at a main meal might. This distinction—between treats consumed as "additions" versus replacements—substantially affects daily energy balance.

Additionally, foods perceived as "bad" or inconsistent with a person's self-image may prompt different compensation patterns than foods perceived as aligned with their dietary identity. This suggests psychological and contextual factors, not just physiological satiety, influence compensation responses.

Incomplete Compensation and Energy Surplus

Research consistently documents that compensation is often incomplete. When individuals consume additional energy from discretionary foods, they frequently do not reduce other intake sufficiently to offset this addition. The result is a net increase in daily energy intake.

This incomplete compensation is particularly pronounced for treats consumed as additions to regular meals and snacks rather than replacements. A person who adds a chocolate bar to their usual intake does not typically reduce other eating by an equivalent amount. Thus, total daily energy increases.

The practical implication is clear: frequent consumption of discretionary foods in addition to regular eating patterns accumulates to measurable net energy surplus over time. A person consuming 200 additional calories from treats daily, with only 50–80 calories of compensation, faces a net daily surplus of 120–150 calories—equivalent to 12,000–15,000 calories monthly.

Chronic Compensation and Adaptation

Beyond acute, single-day responses, research examines chronic patterns over weeks or months. Long-term studies of compensation reveal that while some adaptation occurs, complete compensation rarely emerges. People do not indefinitely maintain compensatory intake restriction; over time, energy intake often drifts toward higher levels.

Additionally, adaptation effects are common. If a person consistently consumes a treat, the initial compensatory response may diminish over time as their body adapts to this new baseline intake pattern. What begins as partial compensation may become minimal compensation with chronic exposure.

This adaptation effect has implications for how discretionary food consumption patterns established early in life may become entrenched, with progressively less compensation as the pattern becomes habitual.

Individual Variation in Compensation Ability

Substantial individual variation exists in compensation capacity. Some individuals demonstrate near-perfect compensation to added energy; others show minimal compensation across contexts. This variation is partly physiological (differences in satiety sensitivity, hormonal regulation) and partly behavioural and psychological (individual eating patterns, responses to food cues).

Research documents that individuals with strong compensation abilities may consume discretionary foods with minimal impact on total daily energy balance, while those with weak compensation mechanisms face greater challenges. This individual variation is one reason why population-level recommendations may not predict individual outcomes.

Context and Compensation

The surrounding context—stress, sleep, environmental cues, eating location, and social factors—influences compensation responses. Stress and fatigue appear to reduce compensation capacity, meaning that energy surplus from treats is more likely to accumulate when a person is stressed or sleep-deprived. Conversely, in relaxed, controlled settings, compensation may be more robust.

Environmental food cues and the presence of other palatable foods reduce compensation. In "food-rich" environments (offices with frequent treats, homes stocked with snacks), compensation mechanisms may become overwhelmed or habituated, reducing their effectiveness.